fig. 1. Duncan Grant, Lydia Lopokova, ca 1923. Oil on canvas.

Copyright Estate of Duncan Grant. All rights reserved, DACS 2020.

Courtesy The Provost and Scholars of King’s College, Cambridge.

An extract from a forthcoming academic publication by Dr Sophie Pickford (King’s College, Cambridge).

Duncan Grant’s captivating portrait of Ballets Russes prima ballerina Lydia Lopokova, currently hanging in the WE ARE HERE: Women in Art at Cambridge Colleges exhibition at The Heong Gallery, was painted in 1923, a few months after Lydia had turned 30 (fig. 1).[1] It depicts her in three-quarter length, wearing a blue empire-line dress, a gold, patterned shawl draped over her long gloves. The painting was inspired by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ Mademoiselle Caroline Rivière (1806), a photograph of which Duncan kept in his studio at Charleston (fig. 2).[2] Duncan is known to have designed the dress Lydia wears in this famous portrait, but until now the exact circumstances of its design have been shrouded in mystery. The answer lies in an intriguing confluence of Bloomsbury art, American-style post-war revue, and the Russian Ballet.

Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Lydia was born in St. Petersburg in 1892 where she trained at the Imperial Ballet School. She first became a member of the Ballets Russes in 1910, and, on their arrival in post-war London in 1918, became a key point of contact between Bloomsbury and the ballet. Fascinated by the groundbreaking music, art, and movement of the eclectic Russian troupe, Bloomsbury became quickly entwined, both socially and artistically, with the ballet. The Ballets Russes’ influence rippled through the group’s creative output and is visible in their art, literature, relationships, and general way of living throughout the 1920s and into the 1930s. In particular, Lydia became close to the celebrated economist and central member of the Bloomsbury Group, John Maynard Keynes, leading to their marriage in 1925. The relationship surprised and shocked Maynard’s friends, who had earmarked him as a life-long homosexual.

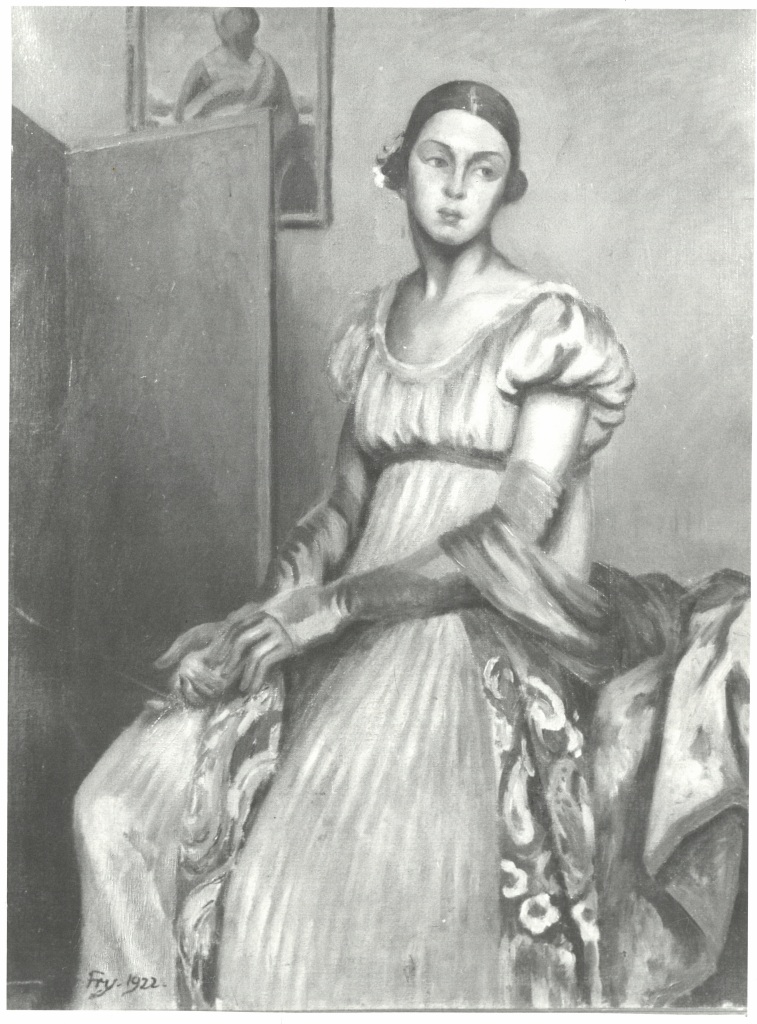

Duncan was not the only Bloomsbury artist to depict Lydia in her blue, empire line dress in the early 1920s. Roger Fry produced a poor companion piece to Grant’s Ingres-inspired work, exhibited at his one-man show at the Independent Gallery in April 1923 (fig. 3). Damned for its ‘cloying prettiness’ by the Observer, and labeled ‘ridiculous’ by Cecil Beaton, Fry’s work was not a success.[3] Vanessa Bell also painted Lydia around 1923, though in different attire. The painting, the whereabouts of which are unknown, was exhibited in the 1923 London Group Spring exhibition. The canvas was ‘retouchéd’ by Duncan. ‘I expect she wanted it badly,’ Vanessa wrote.[4] In addition to these key Bloomsbury figures, Lydia, as a leading ballerina, was painted or sketched by numerous other artists over the years, including Pablo Picasso, Christopher Wood, William Roberts, Walter Sickert, Dora Carrington, and August John. Grant himself produced several other portraits of Lydia in the early 1920s, including an oil portrait of her dancing in his 1922 Scotch Reel costume, and various sketches.[5]

On 27 January 1923, Lydia appeared on the Royal Opera House stage alongside her Ballets Russes colleagues Léonide Massine, Leon Woizikovsky, Ninette de Valois, Lydia Sokolova, and Thadée Slavinsky. Together, they danced in the Anglo-American revue, You’d be Surprised. The première of this clumsily-entitled production had been delayed, the first of a series of problems to plague the staging of this unfortunate work. Featuring a star-studded line-up drawn from America, Russia, and England, the revue was described as a ‘Jazzaganza’ in two acts with a number of ‘surprises’ or scenes. Produced by American one-time juggler Jean Bedini, and presented by Australian-born British theatre king Sir Oswald Stoll, the show had all the initial trappings of success.[6] George Robey, the popular English comedian and music hall performer, led the entertainment, which was heavily advertised in the national press.[7]

Lydia’s contribution to this extravaganza was a ‘miniature ballet with a Mexican setting’, entitled Togo, or The Noble Savage, featuring costumes by Duncan. This short work appeared alongside a Chinese dance by Léonide Massine, a number featuring Lydia dressed as a chicken, and various other musical and theatrical ‘surprises’. You’d be Surprised, despite its poor reception, ran for several months, marking Grant’s second foray into costume design for a Ballets Russes offshoot production, following his work for Lydia’s Scotch Reel in 1922.[8]

On 21 January 1923, prior to the première of You’d be Surprised, Lydia wrote to Maynard, ‘We tried on costumes for 3 solid hours, so much detail to attend to. Vanessa, Duncan, Massine all had something to say. My Mexican is very good…’[9] The first performance was originally scheduled for 24 January, but it was pushed back to the 27th. Finally, on 26 January, the eve of the première, Lydia reported to Maynard that ‘Last night Duncan showed my costume, Empire suitable for my proportions, blue, simple not short, but when I move all the legs become very visible.’[10] The Empire cut of the dress corresponds to a sketch Grant produced for the Togo costumes, the whereabouts of which are currently unknown, though other aspects of the design, such as the neck-line and sleeves, are different.

Closer to Lydia’s description of her costume than Grant’s sketch for Togo is the dress Lydia wore in Grant’s 1923 portrait, based on Ingres’s Mademoiselle de la Rivière. The blue colour, Empire cut and length of the dress in both Grant’s portrait and Fry’s companion work correspond perfectly with the description in Lydia’s letter. Furthermore, Milo Keynes recalls in his article, ‘Portraits of Lopokova’, that ‘Grant designed a dress for Lydia in the style of Ingres’s Mlle Rivière, and both he and Fry painted her that year in this dress at the same sittings,’ confirming Grant as the designer of the dress Lydia wore in the portrait.[11] Milo Keynes dates these events to 1922, corresponding to the date on Fry’s portrait. Grant’s version, on show at the Heong Gallery, is instead dated 1923 on the canvas.[12] Neither painting was exhibited until 1923, and it is highly likely that both works were painted early that year after Duncan designed Lydia’s dress for Togo.[13]

The mysterious blue dress in Grant’s famously beautiful 1923 portrait of Lydia is, therefore, a testament not only to the ballerina’s relationship with the Bloomsbury Group, but also to Grant’s involvement with Ballets Russes offshoot productions in the early 1920s. It speaks of Ingres, of American-style revue and a post-war desperation to fill theatre seats, of Lydia and Maynard’s blossoming relationship, and, perhaps most importantly, of the ever-increasing artistic collaboration between Bloomsbury and the ballet.

[1] Grant’s portrait of Lydia was exhibited in his Independent Gallery exhibition in June 1923, from which it was bought by Maynard, and subsequently bequeathed in his will to King’s College, Cambridge in 1946.

[2] The Charleston Trust, CHA/PH/296.

[3] Observer, 8 April 1923, quoted in F. Spalding, Roger Fry: Art and Life, London 1980, p.226; Cecil Beaton quoted in M. Keynes, ‘Portraits of Lopokova’ in M. Keynes, ed. 1983, p.199.

[4] Vanessa Bell (VB) to Duncan Grant (DG), [21 April 1923], Tate Gallery Archive (TGA) 20078/1/44/116.

[5] In the early 1940s Duncan painted Lydia’s portrait in a feigned oval, now hung at the National Portrait Gallery.

[6] Oswald Stoll presented the production on behalf of the Alhambra Company. See Royal Opera House, Covent Garden programme, King’s College Cambridge Modern Archive (KCC), LLK/1/4/1/102.

[7] George Robey’s real name was Sir George Edward Wade, CBE. Quentin Bell recalls how he would ‘go to the Coliseum with tickets given us by Lydia to see her transformed, etherealized, almost unrecognizably lovely upon the stage. We enjoyed this tremendously, although I cannot say that we didn’t enjoy George Robey and Little Titch with equal passion…’, Q. Bell, ‘Bloomsbury and Lydia,’ in Lydia Lopokova, ed. M. Keynes, London 1983, p.88.

[8] You’d be Surprised ran until mid-April at the Opera house before moving to the Alhambra. Togo was cut before the transfer.

[9] LL to JMK, 21 January 1923, KCC JMK/PP/45/190/13, reproduced in Hill & Keynes 1989, pp.75.

[10] LL to JMK, 26 January 1923, KCC JMK/PP/45/190/13, reproduced in Hill & Keynes 1989, pp.75-6.

[11] M. Keynes, ‘Portraits of Lopokova’ in M. Keynes, ed., Lydia Lopokova, p.198.

[12] Grant’s portrait of Lydia is signed and dated under the frame ‘D Grant 1923’. Roger Fry’s companion portrait is signed and dated ‘Fry. 1922.’

[13] Duncan Grant’s painting was exhibited at the Independent Gallery in June 1923; Roger Fry’s portrait was exhibited at the Independent Gallery in April 1923.